image banks

--l'assiette au beurre

--Les Quatre Saisons de la Kultur

|

|

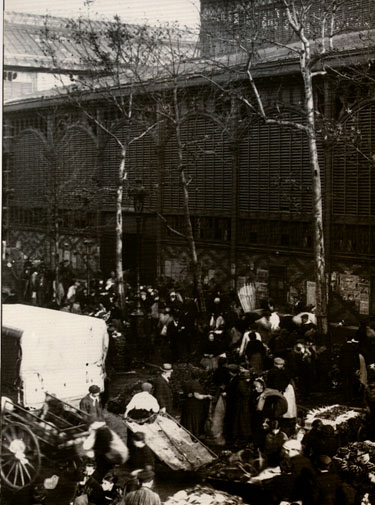

Unloading was in progress all along the Rue du Pont Neuf, the vehicles being drawn up close to the edge of the footways, while their teams stood motionless in close order as at a horse fair. Florent felt interested in one enormous tumbrel which was piled up with magnificent cabbages and had only been backed to the curb with the greatest difficulty. Its load towered above a lofty gas lamp whose bright light fell full upon the broad leaves which looked like pieces of dark green velvet, scalloped and gaufered. A young peasant girl, some sixteen years old, in a blue linen jacket and cap, had climbed on to the tumbrel, where, buried in the cabbages to her shoulders, she took them one by one and threw them to somebody concealed in the shade below. Every now and then the girl would slip and vanish, overwhelmed by an avalanche of the vegetables, but her rosy nose soon reappeared amidst the teeming greenery, and she broke into a laugh while the cabbages again flew down between Florent and the gas lamp. He counted them mechanically as they fell. When the cart was emptied he felt worried.

The piles of vegetables on the pavement now extended to the verge of the roadway. Between the heaps, the market gardeners left narrow paths to enable people to pass along. The whole of the wide footway was covered from end to end with dark mounds. As yet, in the sudden dancing gleams of light from the lanterns, you only just spied the luxuriant fullness of the bundles of artichokes, the delicate green of the lettuces, the rosy coral of the carrots, and dull ivory of the turnips. And these gleams of rich color flitted along the heaps, according as the lanterns came and went. The footway was now becoming populated: a crowd of people had awakened and was moving here and there amid the vegetables, stopping at times, and chattering and shouting. In the distance a loud voice could be heard crying, «Endive! who's got endive?" The gates of the pavilion devoted to the sale of ordinary vegetables had just been opened; and the retail dealers who had stalls there, with white caps on their heads, fichus knotted over their black jackets, and skirts pinned up to keep them from getting soiled, now began to secure their stock for the day, depositing their purchases in some huge porters' baskets placed upon the ground. Between the road way and the pavilion these baskets were to be seen coming and going on all sides, knocking against the crowded heads of the bystanders, who resented the pushing with coarse expressions, while all around was a clamor of voices growing hoarse by prolonged wrangling over a sou or two. Florent was astonished by the calmness which the female marketgardeners, with bandannas and bronzed faces, displayed amidst all this garrulous bargaining of the markets.

Behind him, on the footway of the Rue Rambuteau, fruit was being sold. Hampers and low baskets covered with canvas or straw stood there in long lines, a strong odor of over-ripe mirabelle plums was wafted about.