units

conclusions

image banks

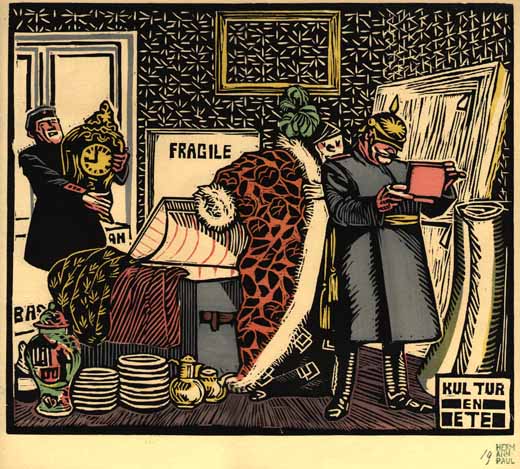

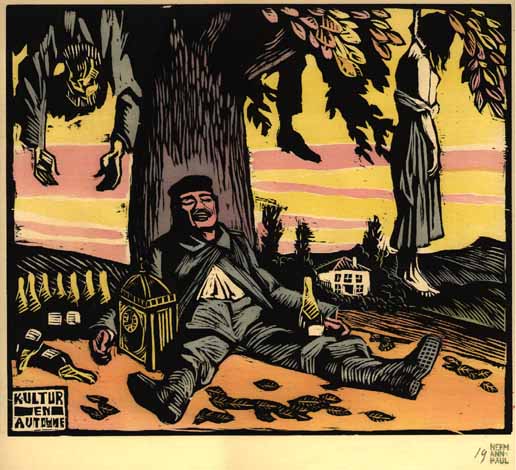

--l'assiette au beurre

--Les Quatre Saisons de la Kultur

|

|

The “Theory of Terror: “

On August 28, Hugh Gibson, First Secretary of the American Legation,

accompanied by his Swedish and Mexican colleagues, went to Louvain to see

for themselves. Houses with blackened walls and smoldering timbers were

still burning; pavements were hot; cinders were everywhere. Dead horses

and dead people lay about. One old man, a civilian with a white beard,

lay on his back in the sun. Many of the bodies were swollen, evidently

dead for several days. Wreckage, furniture, bottles, torn clothing, one

wooden shoe were strewn among the ashes. German soldiers of the IXth Reserve

Corps, some drunk, some nervous, unhappy, and bloodshot, were routing inhabitants

out of the remaining houses so that, as the soldiers told Gibson, the destruction

of the city could be completed. They went from house to house, battering

down doors, stuffing pockets with cigars, looting valuables, then plying

the torch. As the houses were chiefly of brick and stone, the fire did

not spread of itself. An officer in charge in one street watched gloomily,

smoking a cigar. He was rabid against the Belgians, and kept repeating

to Gibson: "We shall wipe it out, not one stone will stand upon another!

Kein stein auf einander!—not one, I tell you. We will teach them to respect

Germany. For generations people will come here to see what we have done!"

It was the German way of making themselves memorable.

In Brussels the Rector of the University, Monseigneur de Becker,

whose rescue was arranged by the Americans, described the burning of the

Library. Nothing was left of it; all was in ashes. When he came to the

word "library"—bibliothèque—he could not say it. He stopped, tried

again, uttered the first syllable, "La bib—" and unable to go on, bowed

his head on the table, and wept. (...)

Destruction of cities and deliberate, acknowledged war on noncombatants

were concepts shocking to the world of 1914. In England editorials proclaimed

"The March of the Hun" and "Treason to Civilization." The burning of the

Library, said the Daily Chronicle, meant war not only on noncombatants

"but on posterity to the utmost generation." (...)

Why did the Germans do it? people asked all over the world. "Are

you descendants of Goethe or of Attila the Hun?" protested Romain Rolland

in a public letter to his former friend Gerhart Hauptmann, Germany's literary

lion. King Albert in conversation with the French Minister thought the

mainspring was the German sense of inferiority and jealousy: "These people

are envious, unbalanced and ill-tempered. They burned the Library of Louvain

simply because it was unique and universally admired" —in other words,

a barbarian's gesture of anger against civilized things. Valid in part,

this explanation overlooked the deliberate use of terror as prescribed

by the Kriegsbrauch, "War cannot be conducted merely against the combatants

of an enemy state but must seek to destroy the total material and intellectual

(geistig) resources of the enemy." To the world it remained the gesture

of a barbarian. The gesture that was intended by the Germans to frighten

the world—to induce submission—instead convinced large numbers of people

that here was an enemy with whom there could be no settlement and no compromise.

From: Barbara Tuchman: The Guns of August