- the fantastic E.T.A. Hoffmann

-

syllabus

-

Bosch

- Bruegel

- Arcimboldo

- Friedrich

- Fuseli

- Grandville

- Goya

- Grünewald

- .....

- Hoffmann

- unit two

- unit three

"This violin", said Krespel, when I asked him about it, "is a very remarkable instrument by an unknown master, probably of the time of Tartini. I am convinced there is something special about the way it is constructed and that if I took it to pieces I should learn a secret I have long sought to discover, but - laugh at me if you will - this dead thing, upon which only I can bestow life and voice, often speaks to me of itself in the strangest fashion, and when I first played it, it seemed as though this instrument was a somnambulist and I only the mesmerizer who persuades her into speech. Do not think I am so foolish as to set any store by such fantasies; yet it is a strange fact that I have never been able to bring myself to dismember that foolish, lifeless object. I am now glad I didn't do so, for since Antonia has been here I have played to her sometimes on this violin. Antonia loves to hear it, she loves to hear it very much."

Except at lunchtime, we, my brothers and sisters and I, saw little of

our father all day. Perhaps he was very busy. After supper,

which was, in accordance with the old custom, served as early as seven

o'clock, all of us, our mother as well, went into our father's study and

sat around a table. Our father smoked and drank a large glass of

beer. Often he told us strange stories and became so excited over

them that his pipe went out and I had to relight it for him with a burning

spill, which I found a great source of amusement. But often he handed

us picture books, sat silent and motionless in his armchair, and blew out

thick clouds of smoke, so that we were all enveloped as if by a fog.

On such evenings our mother became very gloomy, and the clock had hardly

struck nine before she said: "Now, children, to bed, to bed! The

sandman is coming." On these occasions I really did hear something

come clumping up the stairs with slow, heavy tread, and knew it must be

the sandman. Once these muffled footsteps seemed to me especially

frightening, and I asked my mother as she led us out: "Mama, who is this

sandman who always drives us away from Papa? What does he look like?"

"There is no sandman, my dear child," my mother replied. "When I

say the sandman is coming, all that means is that you are sleepy and cannot

keep your eyes open, as though someone had sprinkled sand into them."

My mother's answer did not content me; and in my childish mind there unfolded

the idea that she had denied the sandman's existence only so that we should

not be afraid of him, for I continued to hear him coming up the stairs.

Bursting with curiosity to learn more about this sandman, and of his connections

with us children, I at last asked the old woman who looked after my youngest

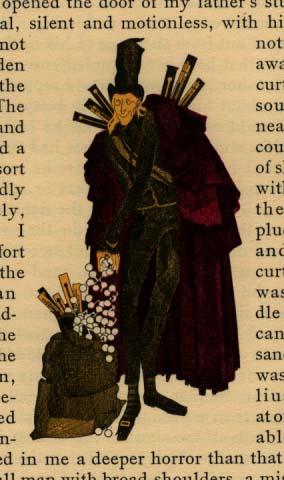

sister what sort of a man a sandman was. "Oh Nat," she replied, "don't

you know that yet? It is a wicked man who comes after children when

they won't go to bed and throws handfuls of sand in their eyes, so that

they jump out of their head all bloody, and then he throws them into his

sack and carries them to the crescent moon as food for his little children,

who have their nest up there and have crooked beaks like owls and peck

up the eyes of the naughty children." The image of the cruel sandman

now assumed hideous detail within me, and when I heard the sound of clumping

coming  up

the stairs in the evening I trembled with fear and terror. My mother

could get nothing out of me but the cry "The sandman! the sandman!" stammered

out in tears. I was the first to run into the bedroom on the nights

he was coming, and his fearsome apparition tormented me till dawn.

I was already old enough to realize that the tale the old woman had told

me of the children's nest in the moon could not be true; nevertheless,

the sandman himself remained a dreadful spectre; and I was seized with

especial horror whenever I heard him not merely come up the stairs but

wrench open the door of my father's study and go into it. There were

times when he stayed away for many nights; then he would come all the more

frequently, night after night. This continued for some years, but

never could I accustom myself to the uncanny ghost: the image of the cruel

sandman never grew paler within me. What it could be that he had

to do with my father began to engage my imagination more and more.

An invincible timidity prevented me from asking my father about it; but

to investigate the mystery myself, to see the fabled sandman myself - this

desire grew more and more intense as the years passed. The sandman

had started me on the road to the strange and adventurous that so easily

find a home in the heart of a child. I liked nothing more than to

read or listen to gruesome tales of kobolds, witches, dwarfs, and so on;

but over all of them there towered the sandman, and I used to draw the

strangest and most hideous pictures of him on tables, cupboards and walls

everywhere in the house. *********

up

the stairs in the evening I trembled with fear and terror. My mother

could get nothing out of me but the cry "The sandman! the sandman!" stammered

out in tears. I was the first to run into the bedroom on the nights

he was coming, and his fearsome apparition tormented me till dawn.

I was already old enough to realize that the tale the old woman had told

me of the children's nest in the moon could not be true; nevertheless,

the sandman himself remained a dreadful spectre; and I was seized with

especial horror whenever I heard him not merely come up the stairs but

wrench open the door of my father's study and go into it. There were

times when he stayed away for many nights; then he would come all the more

frequently, night after night. This continued for some years, but

never could I accustom myself to the uncanny ghost: the image of the cruel

sandman never grew paler within me. What it could be that he had

to do with my father began to engage my imagination more and more.

An invincible timidity prevented me from asking my father about it; but

to investigate the mystery myself, to see the fabled sandman myself - this

desire grew more and more intense as the years passed. The sandman

had started me on the road to the strange and adventurous that so easily

find a home in the heart of a child. I liked nothing more than to

read or listen to gruesome tales of kobolds, witches, dwarfs, and so on;

but over all of them there towered the sandman, and I used to draw the

strangest and most hideous pictures of him on tables, cupboards and walls

everywhere in the house. *********

Can you understand, Lothar, the true inwardness of this adventure? A raging fever took hold of me, and for six weeks I hovered between life and death: in my delirious fits I always imagined I saw the sandman in the shape and features of Coppelius. But that is not the most terrible part of my story. Listen again. For a year nobody had seen Coppelius, and everyone thought he had left the town. Little by little my father had recovered his cheerful spirits and his customary ways of tranquillity and paternal affection. But one night, as nine o'clock struck from the neighbouring belfry, we heard the door of the house creak on its hinges, and footsteps as heavy as a hammer on the anvil began to come upstairs. "It is Coppelius!" said my mother, turning pale. "Yes, it is Coppelius." repeated my father brokenly, and sinister visions flocked upon me on every hand. *********

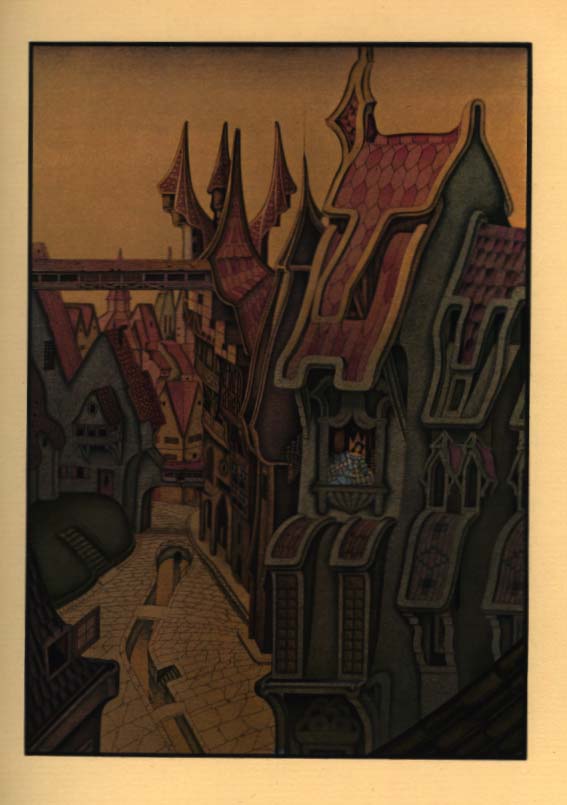

Nathaniel

was very astonished when he arrived back at his lodgings and saw that the

whole house had been burned down, so that only the naked charred walls

still stood amid the rubble. Although the fire had broken out in

the laboratory of the chemist who lived on the lower floor, and the house

had thus burned from the ground upwards, his valorous and agile friends

had succeeded in getting to Nathaniel's room, which lay on the upper floor,

in time to rescue his books, manuscripts and instruments. They had

transported everything, unharmed, to another house, and there taken a room,

which Nathaniel straightaway proceeded to occupy. It did not seem

to him especially noteworthy that he now lived opposite Professor Spalanzani,

nor did he think it anything remarkable when he noticed that the window

of his room gave directly on to the room in which Olympia often sat alone,

so that he could clearly recognize her figure, though the lineaments of

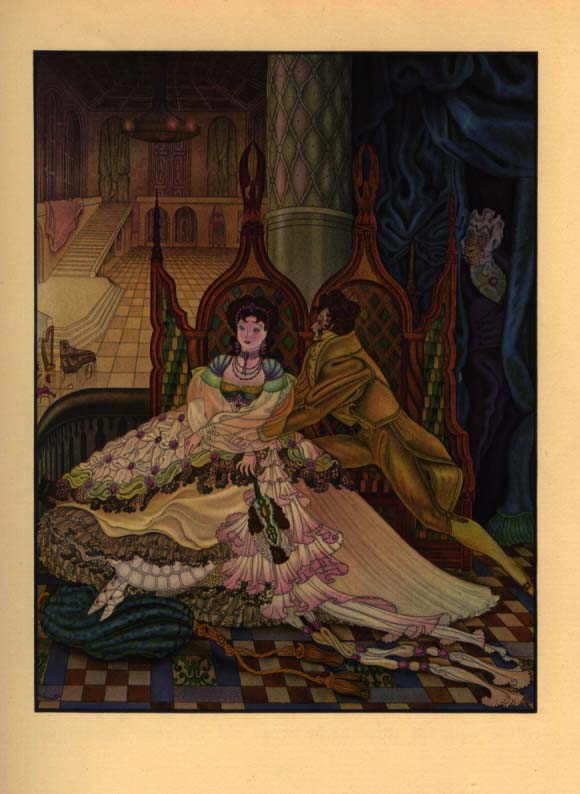

her face remained indistinct. He was, however, finally struck by

the fact that Olympia would often sit for hours on end, altogether unoccupied

at a little table, in the same posture as that in which he had once discovered

her through the glass door, and that she was quite clearly gazing across

at him with an unmoving stare. He was also obliged to admit that

he had never seen a lovelier figure. Nevertheless, with Clara in

his heart he remained wholly indifferent to the stiff, rigid Olympia: only

now and then did he glance fleetingly over his book across to the beautiful

statue - that was all.

Nathaniel

was very astonished when he arrived back at his lodgings and saw that the

whole house had been burned down, so that only the naked charred walls

still stood amid the rubble. Although the fire had broken out in

the laboratory of the chemist who lived on the lower floor, and the house

had thus burned from the ground upwards, his valorous and agile friends

had succeeded in getting to Nathaniel's room, which lay on the upper floor,

in time to rescue his books, manuscripts and instruments. They had

transported everything, unharmed, to another house, and there taken a room,

which Nathaniel straightaway proceeded to occupy. It did not seem

to him especially noteworthy that he now lived opposite Professor Spalanzani,

nor did he think it anything remarkable when he noticed that the window

of his room gave directly on to the room in which Olympia often sat alone,

so that he could clearly recognize her figure, though the lineaments of

her face remained indistinct. He was, however, finally struck by

the fact that Olympia would often sit for hours on end, altogether unoccupied

at a little table, in the same posture as that in which he had once discovered

her through the glass door, and that she was quite clearly gazing across

at him with an unmoving stare. He was also obliged to admit that

he had never seen a lovelier figure. Nevertheless, with Clara in

his heart he remained wholly indifferent to the stiff, rigid Olympia: only

now and then did he glance fleetingly over his book across to the beautiful

statue - that was all.