The Dead in Love (excerpts)

One morning I was sitting by her bedside, eating my breakfast upon a

little table so as not to leave her for a moment. As I was slicing some

fruit, I accidentally cut myself with the knife and made a rather deep

gash in my finger. The blood flowed instantly from the wound, and several

purple drops spurted onto Clarimonde. Her eyes lit up, her features took

on an expression of fierce, savage delight that I had never before seen

in her. She leaped from the bed with animal agility, with the nimbleness

of a cat or monkey, and threw herself upon my wound, which she began sucking

with an air of unutterable pleasure. She sipped the blood slowly and with

great care, like an epicure savoring a Xeres or Syracuse wine; her

green eyes were half closed, and her round pupils had become slits. Now

and then she stopped to kiss my hand, then pressed her lips again to the

lips of the wound so as to draw out a few more red drops. When she saw

that no more blood was flowing, she got up, her eyes shining, her skin

rosier than a Spring dawn, her face full, her hands warm and moist—in a

perfect state of health and more beautiful than ever.

"I will not die! I will not die!" she exclaimed, half mad with joy,

and clinging to my neck, "I will be able to love you a long time. My life

is in yours, and all that I am comes from you. A few drops of your rich

and noble blood, more precious and potent than all the elixirs in the world,

have restored me to life."

This

scene haunted me for a long time, and filled me with strange doubts concerning

Clarimonde. That very evening, when sleep had taken me back to my presbytery,

I found Father Serapion more solemn and anxious than ever. He looked at

me attentively and said, "Not content with losing your soul, you would

lose your body also. Hapless young man, into what snare have you fallen?"

I was startled by the tone in which he uttered these words; but this impression,

intense as it was, was soon dispelled by a hundred other cares and concerns.

One evening, however, I looked in my mirror, the perfidious position of

which she had not reckoned with, and caught a glimpse of Clarimonde who

was pouring some powder into a glass of seasoned wine that she was in the

habit of preparing after dinner. I took the glass, pretended to sip from

it, and then set it down as if to finish it later at my leisure. Availing

myself of a moment when she had her back turned, I poured out its contents

under the table, after which I retired to my room and went to bed, determined

not to sleep but rather to wait and see what would happen. I did not have

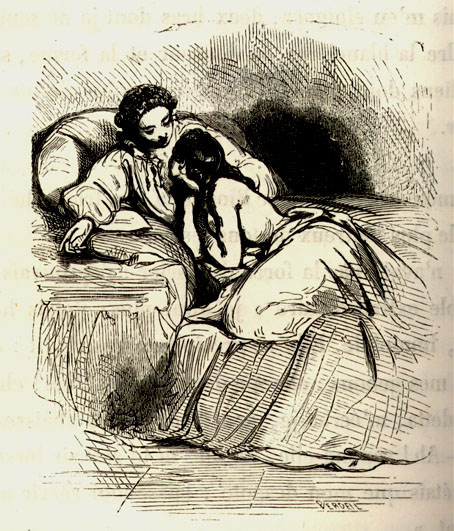

to wait long; Clarimonde entered in her nightdress and, having disrobed,

lay down beside me. When she was satisfied that I was asleep, she bared

my arm and drew a gold pin from her hair. Then she began to whisper

This

scene haunted me for a long time, and filled me with strange doubts concerning

Clarimonde. That very evening, when sleep had taken me back to my presbytery,

I found Father Serapion more solemn and anxious than ever. He looked at

me attentively and said, "Not content with losing your soul, you would

lose your body also. Hapless young man, into what snare have you fallen?"

I was startled by the tone in which he uttered these words; but this impression,

intense as it was, was soon dispelled by a hundred other cares and concerns.

One evening, however, I looked in my mirror, the perfidious position of

which she had not reckoned with, and caught a glimpse of Clarimonde who

was pouring some powder into a glass of seasoned wine that she was in the

habit of preparing after dinner. I took the glass, pretended to sip from

it, and then set it down as if to finish it later at my leisure. Availing

myself of a moment when she had her back turned, I poured out its contents

under the table, after which I retired to my room and went to bed, determined

not to sleep but rather to wait and see what would happen. I did not have

to wait long; Clarimonde entered in her nightdress and, having disrobed,

lay down beside me. When she was satisfied that I was asleep, she bared

my arm and drew a gold pin from her hair. Then she began to whisper

"One drop, just one little red drop, a touch of red at the end of my

needle! ... Since you still love me, I must not die.... Ah, poor love,

I shall drink your beautiful, brilliant, crimson blood. Sleep, my only

treasure, sleep, my god, my child; I will not hurt you, I will take of

your life only what is absolutely vital to my own. If I did not love you

so, I might bring myself to take other lovers whose veins I could drain,

but since I have known you, all others flll me with abhorrence . . . Ah—what

a lovely arm! How plump it is! How white! l I shall never dare to prick

that pretty blue vein." And as she spoke, she wept, and I felt her tears

raining down upon my arm, which she held between her hands. Finally she

plucked up her resolve, pricked me lightly with her needle and began to

suck up the blood that flowed from it. Then, fearing to exhaust me although

she had swallowed scarcely a few drops, she carefully wrapped up my arm

with a little strip of bandage after having rubbed it with an ointment

that immediately closed the wound.

(...)Serapion made the most vehement exhortations, reproaching me severely

for my listlessness and lack of fervor. One day when I had been more agitated

than usual, he told me, 'There is only one way to rid yourself of this

obsession, and although it is extreme, we must resort to it: powerful

evils require powerful remedies. I know where Clarimonde was interred;

she must be exhumed, so that you may see the object of your love in her

true, pitiful condition. You will no longer be tempted to perdition for

the sake of a vile corpse, devoured by worms and about to crumble into

dust; this will surely bring you to your senses." For my part, I

was so weary of this double life that I assented wishing to find out, once

and for all, whether it was the priest or the nobleman who was the victim

of an illusion, I was resolved to kill one of the two men within me to

save the other—or to kill both, for such a life had become unendurable.

Father Serapion provided a pick, a crowbar, and a lantern, and at midnight

we set off toward the cemetery of ***, the location and layout of which

he knew perfectly. After having cast the dull light of the lantern upon

the inscriptions of several tombs, we finally came to a stone half buried

in long grass and weeds and covered with moss and parasites, on which we

deciphered this beginning of an inscription:

Here

lies Clarimonde

Here

lies Clarimonde

Who while she lived

Was lovelier than all the world.

"This is the place," said Serapion, and setting down his lantern, he

slipped the crowbar into the crack in the stone and started to raise it

up. The stone gave way, and he set to work with the pick. I stood watching

him, somber and silent as the night. As for him, bent over his lugubrious

task, he was dripping with sweat, and his rapid, heavy breath was like

a death rattle. It was truly a strange spectacle, and anyone who might

have seen us would have taken us for thieves and profaners of the tomb

rather than for priests of God. Serapion's zeal had something savage and

cruel about it that made him resemble a demon more than an apostle or an

angel, and his large, austere features, sharply outlined in the glimmer

of the lantern, were far from comforting. I felt a cold sweat break out

in beads upon my limbs, and my hair stood painfully on end; in the depths

of my heart I regarded the severe Father's action as a heinous sacrilege,

and I would have been glad if from the dark clouds moving heavily above

us there had issued forth a triangle of flame to reduce him to dust. The

owls perched in cypresses, disturbed by the light of the lantern, beat

heavily upon the glass with their dusty wings, uttering plaintive cries;

foxes yelped in the distance, and a host of ominous sounds emanated from

the silence. Finally Serapion's pick struck against the boards of the coffin,

which re-echoed with a muffled, sonorous sound, with the dreadful reverberation

of the void. He drew back the lid, and I saw Clarimonde, pale as marble,

her hands clasped, her white shroud enveloping her from head to foot. A

tiny red drop glistened like a rose at the corner of her colorless lips.

At this sight, Serapion flew into a fury "Ah, there you are, demon, shameless

courtesan, devourer of blood and gold!" And he sprinkled holy water over

the body and the coffin, making the sign of the cross with his sprinkler.

Poor Clarimonde had no soonèr been touched by the holy dew than

her lovely body fell to dust, and nothing was left but a hideous, shapeless

mass of ashes and half-charred bones. "Behold your mistress, Lord Romuald,"

said the inexorable priest, pointing to the sad remains. "Will you be tempted,

now, to stroll upon the Lido and at Fusina with your beauty?" I bowed my

head; something had just collapsed into a ruin within me. I returned to

my presbytery, and Lord Romuald, lover of Clarimonde, parted at last from

the poor priest with whom he had for so long kept such strange company.

But the following night, I saw Clarimonde. She said to me, as she had that

first time under the church portal, "Unhappy man! Unhappy man! What have

you done? Why did you listen to that stupid priest? Were you not happy?

And what have I done to you, that you should violate my tomb and lay bare

my wretched nothingness? All communication between our souls and our bodies

is henceforth broken. Farewell, you shall mourn me." She vanished into

the air like smoke, and I never saw her again.

Alas. She spoke the truth I have mourned her loss more than once, and

I mourn her still. The peace of my soul has been very dearly bought. All

the love of God was not too much to compensate for her love. There, brother,

is the story of my youth. Never look upon a woman, and walk always with

your eyes upon the ground, for chaste and sober as you may be, a moment

can suffice to make you lose eternity.